A Conversation with Miriam Libicki: WWII Graphic Memoirs

The Canadian cartoonist discusses the art of transforming Holocaust survivor stories into comics.

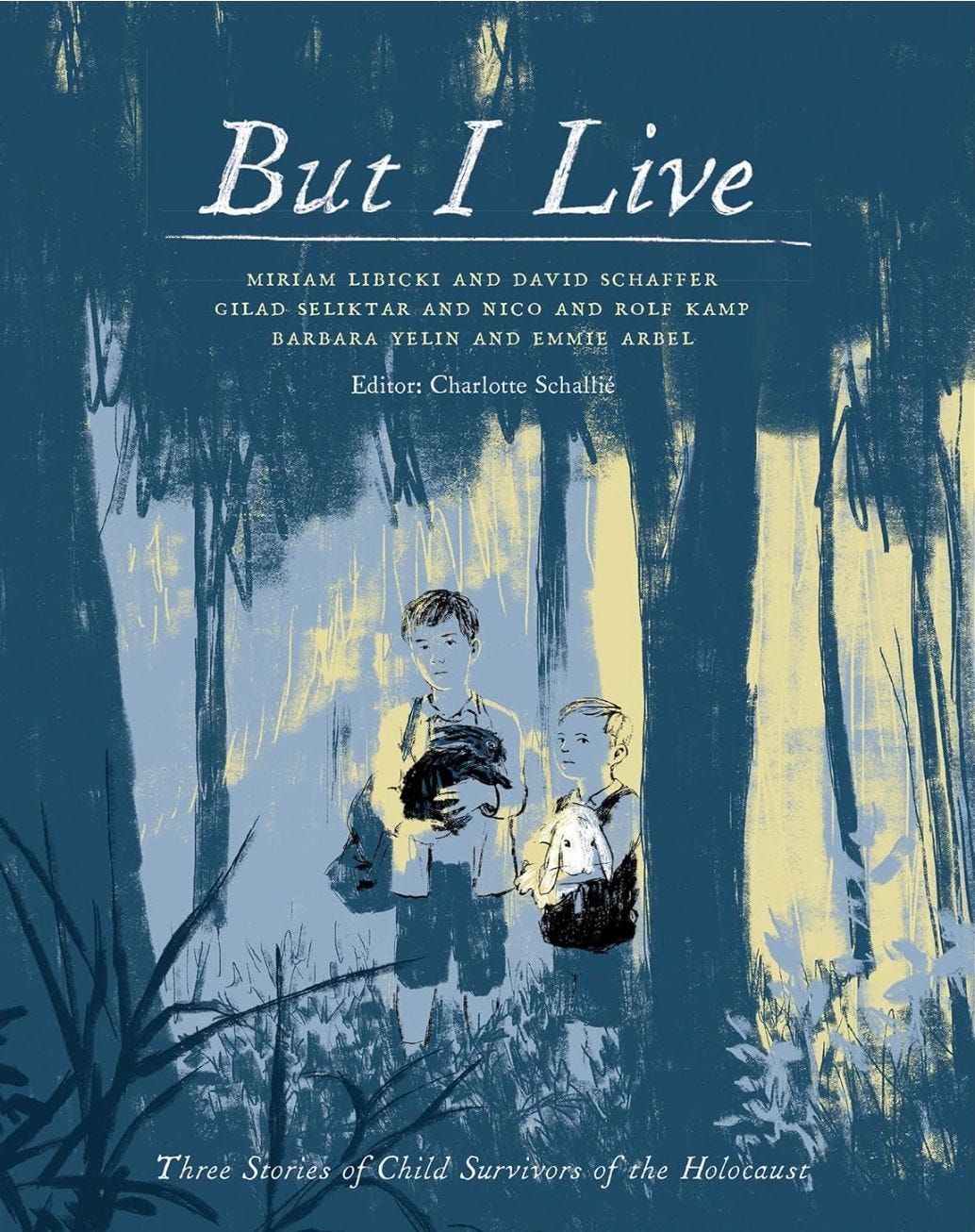

I recently had a fascinating Zoom call with Canadian cartoonist Miriam Libicki. Our conversation ranged from her past collaboration on But I Live: Three Stories of Child Survivors of the Holocaust (2022) to her forthcoming standalone graphic memoir Two Roses. Both are part of the ambitious Survivor-Centered Visual Narrative Project conceived by Professor Charlotte Schallié at the University of Victoria, British Columbia.

The project grew out of Schallié’s observation of how powerful Art Spiegelman’s Maus could be for young readers, even those with little previous interest in history. She envisioned comics as a research and storytelling tool for Holocaust survivors, and with research funding in place, paired artists with survivors whose stories had never been fully told. This reminds me of the work of Positive Negatives which I covered in a blog earlier this year (see article).

But I Live: Three Artists, Four Survivors

The first book, But I Live, brought together three cartoonists—Libicki, Israeli artist Gilad Seliktar, and German artist Barbara Yelin—to collaborate with four Holocaust survivors. Published by University of Toronto Press, it combined memoirs with historical essays, making it an effective teaching tool for classrooms.

The book’s impact was significant. It was adopted into a German nationwide reading program, nominated for an Eisner Award, and continues to be used by professors and teachers.

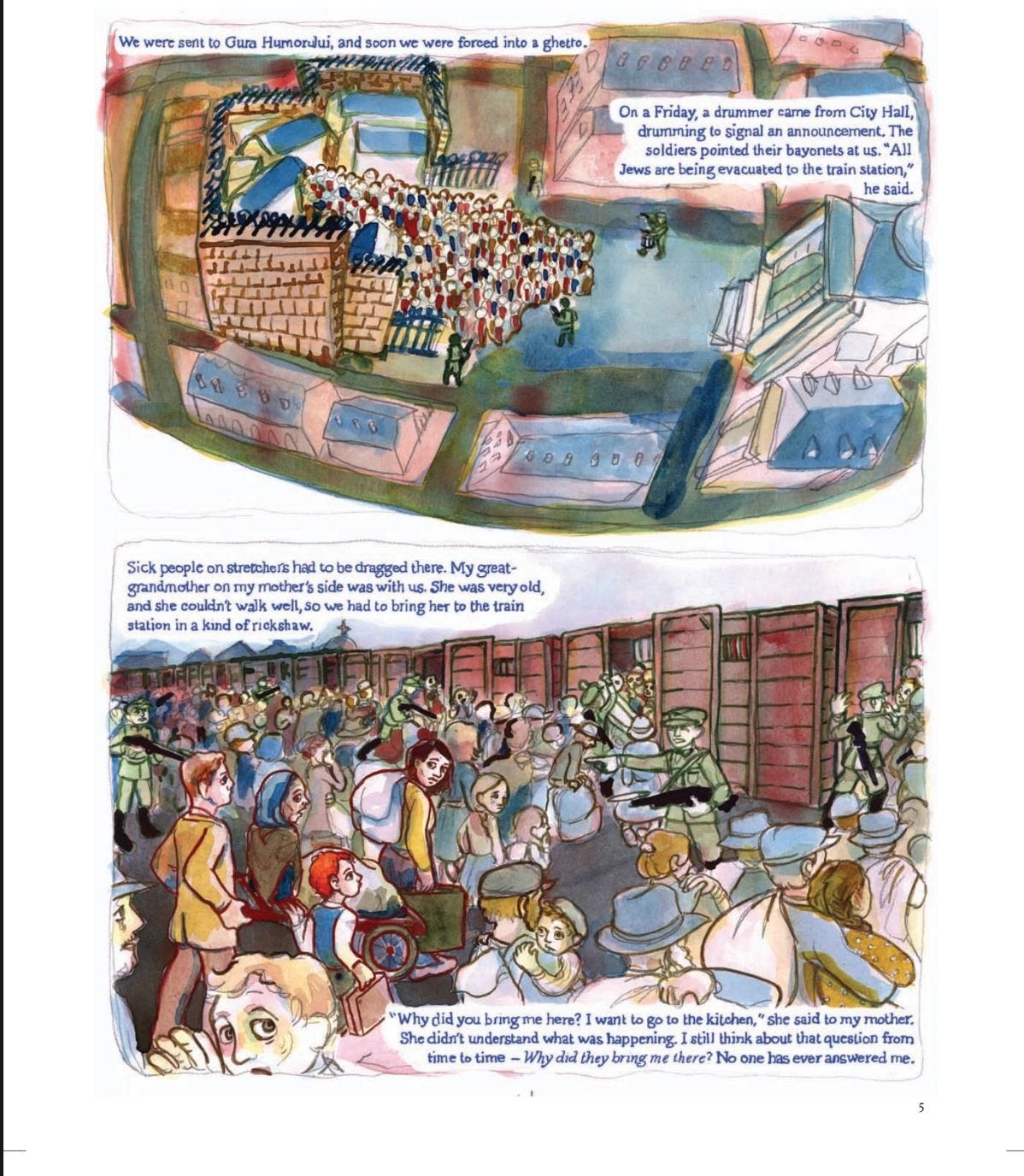

“The story is about how the Romanian Holocaust was highly disorganized. People were expelled, dumped in forests, with no plan and no support. It wasn’t the industrial machine of death—it was chaos.”

Libicki worked with David Schaffer, a survivor in Vancouver. His memories revealed the little-known story of Romania’s Holocaust, where Jews were expelled and left to survive in forests. Unlike concentration camps, this was survival against invisible, arbitrary forces.

Reframing Memory Through Art

Libicki recalls being struck by how Schaffer’s memories felt like something out of dark fairy tales: forests filled with menace, children small against overwhelming powers.

“The way he told the story reminded me of fairy tales—not the good ones, but the German or Slavic ones. Things seem random and capricious. You feel like a tiny person at the mercy of huge forces.”

Using watercolors inspired by early 20th-century children’s illustrators, she sought to evoke the living, threatening natural world. This approach also set her apart from the monochrome charcoal styles often associated with Holocaust art.

Influences

Libicki, herself the grandchild of Holocaust survivors, admitted that Art Spiegelman’s Maus loomed so large for her that she was unsure she could “do something new with it.” She felt grateful that But I Live began as someone else’s initiative, since it allowed her to approach Holocaust testimony from a fresh angle.

In shaping her contribution, she drew on unexpected sources of inspiration, looking to early 20th-century children’s book illustrators such as Kay Nielsen and Arthur Rackham to create the haunting, fairy-tale atmosphere of David Schaffer’s memories. While she acknowledged her work did not directly mimic their styles, their influence helped her find a distinct visual language. She also cited Miriam Katin’s memoir We Are On Our Own as a book she “really loved” and one that may have exerted a subconscious influence on her approach.

Building Stories from Testimony

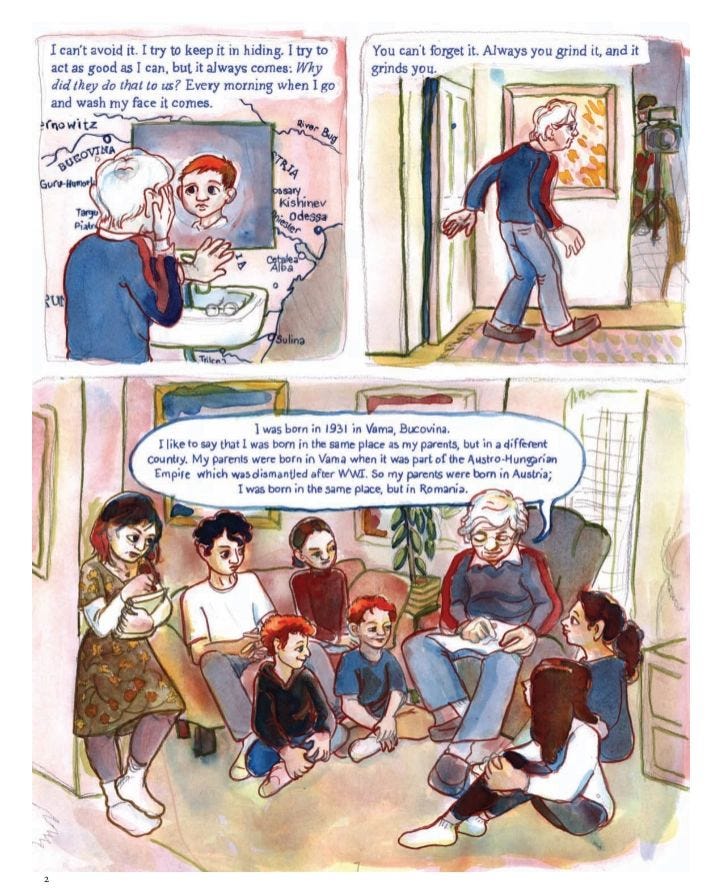

Schaffer lived in Vancouver, which was part of the reason Libicki was paired with him. Yet most of their collaboration took place remotely during Covid, through phone calls and email. Working from transcripts, she shaped a narrative that stayed faithful to his words, noting that “every word in that book is his… the story is his voice.”

To add context beyond what Schaffer described, historian Dr. Alex Korb contributed an essay on the grim realities he never mentioned, such as the prevalence of corpses. The result is a layered reading experience: a child’s perspective of survival set against stark historical analysis.

Collaboration

After meeting briefly at a Leicester University conference in February 2020, the three artists began holding regular Zoom meetings to critique one another’s work. Libicki recalls these sessions as “a very useful part of the process” where they shared pages and gave each other constructive feedback.

Over time, each artist defined a distinct style: Gilad Seliktar leaned into photo-realism, Barbara Yelin used fragmented timelines to convey trauma, and Libicki focused on an immersive child’s-eye perspective rendered in painterly watercolors.

Two Roses: Disguise and Survival

The success of But I Live led to a second round of funding that broadened the project to include testimonies from other genocides. For her next work, however, Libicki returned to the Holocaust with Two Roses, a 65-page standalone volume.

The book tells the story of Rose Lipszyc, who survived by passing as a Polish Catholic alongside her aunt—also named Rose. Pretending to be sisters, they endured forced labour in Germany while living under fragile false identities. The volume also features essays by historians, a behind-the-scenes collage essay by Libicki, and a personal reflection from Lipszyc herself.

Comics, Identity, and Influence

Libicki’s influences range from Phoebe Gloeckner and Will Eisner to Maurice Sendak and Japanese manga such as Akira. She also situates her work within the broader tradition of documentary and autobiographical comics, citing Joe Sacco’s Palestine and Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis as touchstones.

“I’ve always been drawn to first-person stories and particular points of view,” she explains. “Comics are a powerful tool for empathy. Even if you disagree, you can still be compelled by the perspective.”

As a Jewish woman, Libicki emphasizes that identity has never been separate from her art: “I’ve never really subsumed my identity in a project. Even when I collaborate, I bring a lot of myself.”

She also points to the Canadian comics scene as an important source of support. Libicki considers Kate Beaton and the Tamaki cousins trailblazers whose success helped Canada’s arts infrastructure recognize comics as a serious form. This recognition has allowed her to benefit from arts grants and funding—“one way that I’m grateful to be Canadian.” For her, the community is both supportive and open, providing fertile ground for her work to grow.

Looking Ahead

While Two Roses represents one of the high points of her career, Libicki is also developing more personal nonfiction comics.

Reflecting on her trajectory, she sees the Holocaust collaborations as transformative:

“These last two projects have definitely been high points in my career. I feel very privileged to have worked on them, to meet the survivors, and to collaborate so deeply. It’s important work, but it also pushed me creatively. I had real breakthroughs.”

Interview by Jonathan Sandler, Author of THE ENGLISH GI: WORLD WAR II GRAPHIC MEMOIR OF A YORKSHIRE SCHOOLBOY’S ADVENTURES IN THE UNITED STATES AND EUROPE published in April 2022.